“Wherever you are in Georgia, you can see the Caucasus”, said Lasha as we drove west. Looking left out of the car we could see the southern Caucasus mountains, and to the right, the more majestic northern peaks, a long snow-topped ridge in the distance. We were on the first day of three travelling round a pretty substantial area of Georgia, and were seeing and learning a lot. As a result of this trip, I’m calling Georgia the diamond, inset within the borders of the mountains, because it seems to me to be a country of many sharp and distinct differences, many clear cut faces. These faces are, for instance, wildly contrasting scenery, regional varieties of food and wine, different political viewpoints, and so on. Geographically it’s something of a jigsaw, where we travelled from piece to piece and found ourselves in new terrain surprisingly quickly. But mix in with that the different and passionately-held political views, the country’s present political situation, the myriad events and moments of interest we saw, and snapshots of individual characters, and I arrive at my jewel. And as the whole holiday turned out so very special, the diamond representation, as opposed to any lesser stone, is deliberate.

27th May

It takes two flights to get to Georgia. We went via Warsaw, and the choice you have when changing planes is either 50 minutes or 8 hours. 50 minutes is too quick, and besides, I have friends in Warsaw who we wanted to meet. So a 10 o’clock flight from Heathrow meant we were in a cab from Warsaw airport into the city by around 2, Polish time. We drove to the Adam Mickiewicz Institute, for the past 7 years the headquarters of the ICO Orchestra. In fact my work with the ICO was the reason for this holiday destination; of all the cities I’d travelled to, Tbilisi was easily the one I was most enthusiastic about returning to. Easily.

We pulled up outside the Institute and Gosia came out to meet us. She led us to a nearby restaurant, which was very open-spaced, classy, and almost totally empty. The three of us had a wonderful lunch (of a mackerel and rocket starter followed by a beef dumpling in broth, these descriptions do not do the food justice at all), towards the end of which Gosia told us of a few places we might visit in the city – we still had ages before we’d have to go back to the airport. She booked us an Uber and we set off to the old town, to the theatre first. This is the biggest in Europe and is therefore absolutely enormous. Unless I’d misunderstood, and that in fact half of the enormous building is a government department or something, it’s hard to believe the whole thing is just one theatre. But apparently so.

Then a short walk to the old town, the centre of Warsaw, where we had a gentle stroll in and out of the cobbled lanes before settling at a table in the Market Square for a beer. More ambling, towards the river and a few more empty passageways, and we were ready to head back to the airport, though there was plenty of time. It had cost us 50 zloty to come into town, so it was disappointing that when we approached the driver at the head of a taxi rank the charlatan said his fare would be 120 zloty. I laughed, though it’s a shame really, that cab drivers think they can treat people like that, and we wandered elsewhere. We soon found another taxi, parked on his own. He said 70 zloty, and that was much more like it, so we climbed in.

A couple of hours spent very lazily sipping beers – neither of us was particularly energetic or thirsty, certainly not hungry – in a bar, and we headed for the Gate for our 10.25 late night flight to Tbilisi. But there was a hold-up. It looked like a huge group on the flight hadn’t been given their boarding passes yet, and a lot of time was wasted while they handed them out individually as they went up to go through to the plane. In the end this was just one of those flights to be endured, and we sat and failed to sleep in uncomfortable seats for about 3 hours. As we descended to the airport there was a lightning storm off to the right, fortunately far enough away not to trouble our flight, but exciting to watch the flashes in the hills.

We landed at around 5 in the morning, Georgian time. And appropriately, George was there, waiting for us. The driver sent by the tour Company had had to hang around for our delayed flight but he was chirpy enough, and chatted a bit as he drove us from the airport. This particular road has always been a memorable one for me, because of one dog-leg turn. Seems a very unremarkable reason to remember a place, but on so many other cab journeys from airports into ICO cities, I’ve been greeted by the sight of harsh landscapes of ex-Soviet tower blocks – Kiev in the rain was a stand-out gloomy drive – yet the dog-leg in Georgia, which I’d previously always arrived at in the dark, led straight to a shabby, even sleazy-looking street which to me instantly showed great character. Late, late-night shops (early morning in today’s case) which you could see into, neon signs above establishments you couldn’t, even grimy hovels, all were exciting, and compared to the crushing Communist blocks, even uplifting. We were now on the outskirts of the city, and as it isn’t a very big one, we were soon right in the centre. We drove up to Liberty Square in the morning light, a huge roundabout with a plinth and gleaming gold statue of St. George (of course) in the middle. Two minutes later we arrived at our hotel, well-chosen and very central. Our own George drove off, and we would see him a few days later as our guide to the city.

28th May

Of course much of the previous section had been the 28th already, but the day started for real for us at about midday. After a very long day yesterday, with no sleep for a long time, we’d got to the Hotel Citrus at 6am, and promptly flopped into bed and set alarms for 11. Somehow we were both reasonably awake from about 10, but not hurrying anything, we ended up walking out around 12.

The vast majority of this holiday had been paid for several months earlier, in October in fact, a record for us, so all we really had to look after was day-to-day spending money, of which I’d acquired about £1500, plenty more with Helen’s account. So I confidently strolled into a nearby bank to get some initial Georgian lari out. (It’s not one of the easiest conversions to work out, as there are about 3 ½ lari to the pound, so on this trip we rounded up to 4, a bit of a leap, but we knew that things weren’t expensive here so who’s counting?). I thought I’d just check my balance first, and froze as the screen told me I had £15 in the holiday fund. I pressed on, literally, and tried to get £200 out, which ought to see us through to at least halfway through our tour of the country, a few days at least. ‘Insufficient funds available’ said the screen, and my heart stopped again. But my maths had gone wrong, though it took a controlled-panic dash back to the hotel to discover this. After talking to someone in England, it turned out that the initial £15 claim by the cash machine had been just a computer mistake, and me asking for 2000 lari had been my mistake. 2000 lari, by my earlier reckoning, is around £500, not the £200 I’d intended, and that’s simply more than that account lets me withdraw in a day. Phew! So we went back to the bank, I confidently strolled in as before, asked the machine for 800 lari this time, and it paid out. Not the start we needed but we were back in business.

Of course this initial stress put the edge on an already healthy thirst, and Helen spotted a little alleyway and alcove to our left. It was a hot day, Georgia is several degrees hotter than England. That’s not usually saying much, but on this holiday we were lucky with consistently glowing temperatures, glowing but not stifling, it was lovely really. We went up the few yards of alley and took seats at a table in the small courtyard. The waitress brought out our two glasses of Georgian white wine, and cheers! the holiday starts here. Georgian wine is exceptionally good, and this one was a good representative, so it was a lovely (and calming!) first little stop-off of our holiday. I think we had two small glasses each and it was a gorgeous drink. We do stop-offs very well.

We set off back along the main street, Rustaveli Avenue. This is named after Shota Rustaveli, a medieval poet, and how cool is that? A poet, and the Oxford Street of the country is named after him. During our visit to Georgia so many things were pointed out that were named after artists, mostly writers. I think that’s great. This main avenue is wide, and flows down to Liberty Square and the statue of St. George. It’s busy, yet leafy, and only a few yards away from the traffic it’s surprisingly peaceful. Not a street to cross, there are occasional subways, little dark passages which have rather Dickensian subterranean shops along the sides. We walked quite a way up, then turned back when a hotel that I’d previously stayed at proved further away than I thought. Time for lunch.

There were several pavements restaurants and cafes and we stopped at one called Shatre, that looked about our level, not posh at all but just restful, with an interesting menu. Neither of us had the slightest interest in eating anything non-Georgian throughout this entire visit, in fact I now realise it was even unspoken. We did well here, me possibly slightly too well. We started with the Georgian national dish, which is khinkali, dumplings, 6 of them, 3 of cheese, 3 of meat. Also something I’d really looked forward to, strips of aubergine filled with a walnut pesto. I think I ate this every single day of our trip. These were all just hors d’oevres, accompanied by Georgian wine and beer. We’d ordered chakapuli, a Georgian veal and tarragon stew, and veal ribs with ajika, a spicy red sauce. I’d had this on previous visits, but this was the best one. The stew was sensational too, a basket of Georgian bread arrived and we had a great lunch. With the ajika being the best one I’d had I just failed to stop eating, about 9 ribs, and the sauce mopped up with the bread. Hadn’t realised I was that hungry.

We set off in the sun again, very happily full of robust and tasty Georgian food and drink (in a reverse of our usual form, during our entire stay, I gravitated towards the local wine, Helen more the beer), crossing the road by one of the dark subways. We came to a large church I’d noticed on previous visits, but couldn’t go inside as women have to cover their heads, and Helen’s scarf was back at the hotel. We were to find out soon that every church and monastery has a box of scarves just inside the door for anyone to use, but at the moment we didn’t know that. We also came to the National Museum, nice and cool inside, but a visit for another day. We looked briefly in the shop, where a cookbook described the recipe for bazhe, a walnut and garlic sauce similar to the filling of the aubergine strips, in which two interesting and exotic ingredients were blue fenugreek, a Caucasian relative of fenugreek, and marigold.

Following Rustaveli Avenue down to Liberty Square, we then turned back towards the hotel. There was a garden stretching up the hill by the square, so we walked in there, past couples sitting on the many benches, and up through the pine forest-like greenery. There was no gate at the top end, which would have brought us out by our hotel, so we had to go back down, speeding up now as there were distant rumbles of thunder. This was now getting towards early evening, and as the next few days were going to be full on, and giving ourselves more chance to recover from yesterday’s journey, we slipped into the hotel bar for a couple of drinks, then up to our room to finish the day with whatever was on TV and a bottle of wine in an ice bucket. We had a small balcony overlooking the square outside. Bathed in orange light, fir trees stretched right up to the balcony, you could stroke the branch, there were couples on benches, it was a lovely calm evening scene. Though with the thunder still off in the distance, giving that feeling of suspense, of the air hanging, waiting, it was also reminiscent of Lugano, two years ago.

29th May…

…or Day One of our round-Georgia trip. Of course we couldn’t possibly ‘see’ all the country, but we were to cover a lot of ground in the centre and north of the country. Tbilisi is south west, though there’s plenty more of the country further in that direction, so we set off east, across the middle of the country. Our driver was Lasha, who came to our hotel in the morning. A big chap, young, fairly robust and cheerful, he was very easy company, which was great as we were to spend much of the next three days in his car. We’d packed one of the two suitcases, left the other at the hotel for later in the week, and set off.

We left the city via David the Builder Avenue, the main street north. His was a name that came up a lot, as he was the most famous ruler of the country, in the 12th century. He fought various battles against Muslim invaders, won tremendous victories, and in 1122 captured Tbilisi and made it the capital again. Where we were driving to now was the old capital, Mtskheta. This is pronounced Mscater, with a glottal rasp on the c. But the very first stop was the Jvari monastery, high up on a hill overlooking the old city. This area was the birthplace of Christianity in Georgia, in AD 326. A missionary called Nino arrived in pagan Georgia, planted a cross here, and proceeded to convert the queen, then the king. She is now a national icon, and her own grapevine cross can be seen everywhere, often as a flag flying next to the Georgian national flag. Incidentally, in ancient times, the pagan Georgia was actually called Iberia, and there is a link between the Iberia we know, i.e. Spain, as there was a substantial migration from Georgia to the Basque region and Navarra 5000 years ago.

We entered the small monastery, Helen borrowing a scarf from the box, and it was cool, dark and quiet, hushed, despite being full of tourists. We were to visit many such buildings in the next few days, most built with cross dome design, and many of them were square buildings, as opposed to the oblong, nave-to-altar shape. This doesn’t give much floor space, and the centre of the church was a large stone block, covered with tributes and leaves, with a tall cross in the middle (this is what cross dome means, not a dome with a cross on it, as I thought, but a cross inside the church, directly under the dome). This is one of the most important sites in Georgia, overlooking another in the valley below, the old capital. As we left, there were beggars at the car park gate. One thought we were Swiss for some reason, and called out ‘Viva Roger Federer!’. Lasha laughed and said ‘They’re English!’. Immediately the guy shouted back ‘Theresa May!’.

Mtskheta was the capital of Georgia for 1000 years, from 500 BC to 500 AD. We drove down to the valley, also a confluence of two rivers (one being the Mt’k’vari, which flows into Tbilisi then on to the Caspian Sea), and parked near the central Svetitskhoveli cathedral. To get there we had to pass a long street of openly tourist stalls, selling sweets, postcards, Georgian brandy and the national spirit, chacha, Cossack wigs, and all that paraphernalia. A few stalls sold what looked like long pea pods, but in all colours. I asked one lady what they were, and she said ‘Georgian Snickers!’ quite delightedly. Which is what they’re known as here, or certainly sold as. In fact they’re small grapes, encased in a sugary syrup and dried till they’re a sort of extended lollipop. I never did try one. Helen had her own scarf with her by now so as we entered the cathedral, she looked quite the part, with it draped above her head like a Bedouin tribeswoman.

The impressive cathedral, like the monastery on the hill a UNESCO site, is one of the most famous buildings in the country, built in the 11th Century. It’s full of artefacts, tombs, frescoes, bright icons on the walls, and is quite large. There’s a picture of St. Nino on one wall by the door. A lot of the gleaming icons are in fact modern, the originals being kept for safety in museums. This building has survived a lot, attacks from all sorts of invaders over the centuries, and at least one earthquake. Tragically, many of the frescoes here were whitewashed by the Russians in the 1830s, as they prepared for the visit of Czar Nicolas I. He never turned up.

I think it was on the next drive, and hour or more west, that Lasha told us of the Russian occupation of parts of Georgia. He wasn’t talking about the country being a Soviet Republic for 70 years till the wall came down in 1989, no, this is happening now. Two swathes of land, one the north-west corner of the country, the other a large loop stretching as far into the centre as to be a mere 20 miles north of the road we driving on. We had no idea, and Georgians resent the fact that it is so under-publicised, the west hardly knows a thing about it. Russia, right now (and that’s one of the things I found hard to take in) has marched into this country and simply taken over areas, sometimes stealthily at night, moving their barbed fences forward while the locals sleep. We saw a man interviewed on the TV while we were here. He spoke from inside the Russian fence. A few days ago he’d been asleep at home. When he woke up, he was separated from his own farm buildings and stock by a fence. This is just unbelievable, and during the week we certainly got to appreciate exactly what’s going on, and the feelings of the Georgian people about this. One of the waiters at Shatre yesterday was wearing a white T-Shirt with the proud slogan ‘20% of my country is occupied’. Russia did not come out of this holiday well.

Joseph Stalin. So what do we know? What are we taught in England? He was a dictator of the worst kind, a thoroughly evil man who dominated his people for almost 30 years, had over 700,000 of them killed and over a million imprisoned; a monster. He was also Georgian, born in the place we were to visit next, the central Georgian town of Gori. And our specific reason for visiting was to go to the Joseph Stalin Museum. Whoa. There’s a museum for this guy? This was what Helen and I could not understand. Yet we knew we’d have to tread carefully if we were to ask any questions. The museum is there, has been for a long time, so somehow, there’s enough pride in Georgia of Stalin for this to happen. Also hard for us to take in.

At the museum, Lasha bought our tickets – all part of our pre-paid deal – and handed us over to small group and guide, in fact there were only 5 of us. The guide was also a young man, tall, stubble-to-beard, energetic, informative and helpful. There were only two groups going round the museum at this time, us and a much larger group of about 30 people, tourists from somewhere. I didn’t pay them much mind, except that we were forced to. Time after time, our guide and group had to move round the room, pushed by the larger crowd from where we were listening and looking to another section. They almost seemed to be following us, slightly too fast. The guide was a bit irritated by this, but maintained his frustration very well, simply accepting it with a resentful stare at the horde and moving along, mostly carrying on talking; he was excellent. There was a large stateroom where, behind a cord, there was a solid table with a leather chair. In front of the table was an oblong of wooden seats, quite close together. This was Stalin’s actual table at the Kremlin. He sat in that chair, giving his orders to those in the seats. He used those two phones. It was frightening. In cases round the walls were other personal items, his uniform, boots, a chess set. Our guide – we never learnt his name – had told us earlier that Stalin wasn’t his name at all, his name was a much longer and gentler Georgian name. Stalin means ‘Man of Steel’. Nice.

Our guide seemed a reasonable man, and Helen broached the question we’d been wondering about, by asking how he felt about Stalin. ‘Not good’, he said, ’25 million people’ (this is the number of Russians that died in WW2), ‘you can’t forget that’. In a way of asking about the existence of the museum, Helen asked how the Georgian people in general felt about him. It seems it’s generational. Georgia under Stalin, and right up until the big change in 1989, was much wealthier, and the old people remember those good old days, hence monuments and tributes like the museum. To a large part of the population, the man is known as ‘Uncle Joe’. Facts like that are sickening. It seems you can ‘forget’ about the 25 million. But the younger generation are completely opposite, they are ashamed and appalled by him. Yet I got the impression that it was still, even now, a bit dangerous to speak out against him. They may be ashamed and appalled, but they’re outwardly quite calm about it. We explained that we agreed with him, and that we weren’t exactly proud of the British Empire’s efforts in, say, India. He really understood that.

After the main rooms of the museum, we came outside to the grounds, and to a small cabin. This was a reconstruction of the room in which Stalin was born. Somehow, the large group were here before us, going up the steps at the front one by one, to stand briefly in the doorway to see the room. We simply joined in, without any apparent resentment from the larger group. But their guide called out something, and straightaway our guide shouted something back. The visit here, of 30 seconds each inside the cabin, didn’t last long, and we moved on. As we walked away, our guide muttered ‘That’s why I hate the Russians!’. I hadn’t realised the other group were Russian at all. ‘What did she say?’ I asked. ‘She said we were holding up her group’. ‘And what did you say to her?’. ‘I said (now he took on a military tone) ‘If you use more than 2 minutes you will all be shot’’. Blimey. He was furious. ‘She comes to MY country and tell ME what to do!’. He was shaking with anger. This was real; as I said, it’s happening now.

Lastly, we all moved on to walk through Stalin’s personal railway carriage, which was interesting to look at from a historical point of view, but as with everything here, the fact that it is here at all means you’re always aware of the madness, cruelty and genocide that still seems to permeate the whole place. He died 66 years ago.

The two almost confrontationally-opposed views of Stalin and Communism started to give me the idea of the faces of the diamond; all part of the same entity but completely different angles. Truly scary stuff, and so is the situation today.

Lunch, and Lasha drove us to a nice cafe/restaurant in the middle of Gori, which is a fairly open, wide-street sort of place, vaguely downtown American I suppose. We ordered kachapuri, a very popular bread stuffed with cheese (I wonder if there’s a linguistic connection between the end of this word and the puri bread of India). Often it comes flat and folded over, like pancakes, but here we got cigars, and they were delicious. They were a sort of nibble, to go with our beers. For a main course we shared Today’s Special, which was another staple Georgian classic, Chanakhi, which was an iron pan of pork, potatoes, tomatoes, onion, garlic and peppers, totally up our street. About the tomatoes though, I don’t know how it happens but Georgian tomatoes taste better, stronger, sweeter, tastier than anywhere else, and I include the lovely beef tomatoes of Greece. There’s a salad which is ubiquitous here, simply of tomatoes and cucumber, with or without a crushed walnuts dressing. There are a few thinly-sliced red onions incorporated, but that’s it. And I could say the same about the cucumber, it’s without doubt a tastier variety than anywhere else. Perhaps the flesh to watery seed ratio is different, but the flavour is definitely enhanced somehow, and by the end of the week, both of us were ordering this salad to start every meal.

Back on the road, but briefly a turnaround, as we headed out of Gori and drove back north east, towards the Uplistsikhe cave rocks. Before we got there, after the experience and confrontation at the museum, we ventured to ask Lasha his opinion of Stalin. His, being of a young generation, was the same as the guide: he was very anti. Yet like the guide, he was reserved about it. He explained that he was born in 1990, and had therefore no experience of the old Communist rule, and the apparent prosperity of years gone by. But even so, it was a fairly cool No to Stalin, there was no rant, or guilt about his country having spawned one of the worst mass-murderers in history, he stated facts, and that he did not approve. I think at this point we raised again the fact that we weren’t proud of our venture into India, and like the guide, he got that. Perhaps guilt is a particularly British thing. Perhaps it was before his time so he felt no reason for it, which somehow didn’t apply to us and India.

After this discussion, and shortly before we arrived at the cave city, we were happily driving along when he announced ‘This is the Silk Road’. This was a thrilling moment for us. Obviously the B567 or whatever we were on wasn’t literally what he was referring to, but the fact that we were travelling along the route of the famous old trade passage was suddenly an eye-opener (literally for me, drowsy after our lunch), a big Wow! The Silk Road was undoubtedly one of the many reasons we’d come to Georgia, though without any particular plans to find it. It was a fabulous, exotic, hint-of-the-east part of history that happened to pass through the country, and therefore made it very attractive. So to find ourselves on, or even near its path, travelling along with those ancient traders and caravans was a stunning feeling. We both jumped when he said it.

Uplistsikhe is an ancient site of cave dwellings, on a hill overlooking the river, the same Mtkvari river which flows all the way back to Tbilisi, and ends up in the Caspian Sea. It was a prominent town of Georgia, even before Mshketa emerged as the capital in 500BC, that’s how old this place is, it was started in the early Iron Age. That, in this part of the world, means it’s up to 500 years older than Mshketa. (I discovered while writing this that the different ‘Ages’ occurred at different times in different places. For instance the Iron Age is listed as 1200-550 BC in the Ancient Near East, which I suppose is Georgia. But for us backward folk of northern Europe, it was 500 BC- AD 800. Amazing. Makes sense. Once people had discovered iron, I guess their first thought was not to dash off and tell their neighbours all about it.) This sort of close-up history, especially of this sort of vintage, is fascinating to both of us, and we eagerly clambered up the rocks on rough paths after our guide. Again, Lasha had handed over to the local expert, called Tamar, and she led us up towards and through the various formations. These are structures fashioned from the rocks themselves, or large holes, rooms cut into them. At various levels she explained what the rooms were probably used for, granaries, halls, temples, and extraordinarily, a pharmacy, football pitch and theatre! The pharmacy, or apothecary’s store was clear, with a wall with square stone pigeon holes for medicines and herbs to be stored, you could easily imagine the scene. The football pitch not so much, but if she said so, so be it; it was now a small flat ledge with a crevasse right next to it, just off the main street. When I say main street, this was just a stone pathway wider than the others which wound up, around and through the rocks. And the theatre, blimey, I wasn’t expecting that. But you could picture the action on the small flat stage inside a cave mouth. The stage faced out to the viewing area, the world opening out to the hills behind that, there was a backstage area and even a narrow square cut into the side, for props. All this is informed guesswork, of course, said Tamar, but I was happy to go with it. At either side of the stage were holes in the ground, little wells about 3 feet deep. ‘What are these?’ I asked. ‘For whispering’ replied Tamar, and it was a second before I worked it out; these were the ‘wings’! If a performer forgot a line, someone standing in the well would whisper it to them. Again, it stretches the imagination a little, but that’s fun. I called to Helen, who’d missed this last little chat, and pointed to the holes in the ground. ‘What do you think these are for?’ ‘The orchestra?’ she replied cheekily. I did laugh.

On one of the highest areas of the site there was a basilica, a small church, built in the 9th century. The basilica was the prevalent style of church building in Georgia for a long time, until the cross dome style took over. Incredibly, this small, ancient building, high up on these primitive caves, is still used today, it’s an active church. This place is mind-boggling. And as we approached it, Tamar pointed up to the ridge just above the site, and said ‘That’s the Silk Road’. Again the absolute thrill of being able to see and envisage the old pathways, this time along the tops of nearby hills; you could see camels, and merchants dressed in their wares of silk, baskets of spices…

Towards the end of the tour was the market, a small area, but with marked stalls, windows of stone really, where the Silk Road traders would come down to the settlement from the hills and sell their fabulous eastern offerings. It was all so evocative and imaginable. Near this was a secret passage. We descended into a hole in the ground, much bigger than the orchestra pit, with steps leading down into the darkness. This was a clever escape route for the ancient dwellers if they were being overwhelmed by invaders, and was a long clamber down in the dark for them, to emerge next to the river. Today it flowed gently, light-green and shallow in the sunshine. This is, again, the Mt’k’vari river, now in the centre of Georgia.

Amazing stuff, and from here we walked back to the gate and the car. The guide had several times mentioned that future archaeological work at the caves was planned, and I offered her some money, asking if it would help with the funding, which she accepted. There are thousands of women in Georgia called Tamar, after Tamar the Great, ruler of the country from 1184 to 1213. She was such an influential and successful queen that she was actually given the title mepe, which means king.

By the entrance to the site was a refreshment stand, which sold something I’d been wanting to try: wine ice-cream! We’d never heard of this before, and it came as a cornet into which was furled a lilac cone. It was definitely more grapey than winey, and of course that’s bound to be the case, but I dare say there was wine involved somewhere, and it was tasty in the now boiling heat. Up on the open caves it had been warm but breezy, high above the river and surrounding wide countryside, but down by the cars it was pretty heavy now.

So we headed off, back west again now, and soon into a very green forest. This drive was to be a bit of a haul, about 2 ½ hours, and most of this was spent just winding through this lush scenery. Sometimes down by the river on the valley floor, sometimes on higher roads in the trees. At one point we went through a tunnel, which Lasha said was the midpoint between east and west Georgia. Soon after this we stopped briefly at a glade, in a pine forest off the road. It was a very ramshackle set of buildings, almost gypsy-like. Some people were playing loud music and having a party in one of the empty stalls at the back, there were some cafes and seats among the trees by the road. I wandered around a bit, and came across an old wagon like the Wild West, that looked like it had once been a very small bar. I peered in through the cracked windows and heard a rumbling noise. I looked away, and through the trees saw a herd of cows running towards me. It wasn’t a charge, but neither was it an amble, they were aiming for something, and never having met them before I presumed it wasn’t me. As usual, intrigue and interest overrode any fear I should have had, or you could say stupidity held me firmly in the path of the marauding cattle, but with about 20 yards to spare, the leader veered left, towards the road. The rest all followed, and strode headlong onto the tarmac. Fortunately this was not a busy section and no cars were nearby, so the herd passed across into the woods on the other side without any danger, though a few of the stall and cafe owners shouted and tried to impede them. They disappeared into the trees, yet there were a few stragglers, slower cows with less impetus, who trampled down towards me then across the road. But it had certainly taken me, and everyone, by surprise.

Back on the road, it was by this time around 5, and the bright late afternoon light made the colours gorgeous. I say colours, we were surrounded by a bright and beaming green of unripe lime, and I tried many times to take a picture of the all-surrounding trees in this light. Often, by the wayside, we passed long sheds with clay jars, vases, urns and huge pots outside. The pottery is called shrosha and the stretch where these roadside stands were most prevelant was called Shrosha village.

It was still a good hour or so to Kutaisi, where we were to stay, and eat later, and we had 2 more sites to visit. Lasha, in an extremely non-pressure way, mentioned that it would be about 8 by the time we got to the hotel, and that seemed to make the day a little too long, so we took the decision to visit just one of the tour highlights, the Gelati monastery. The world had suddenly changed now, the gleaming forest was behind us, and we were now driving along more commercial roads, more grimy, with shops and garages along the way, and evening was starting to think about stirring itself. However here was where Lasha made his comment about being able to see the Caucasus mountains from anywhere in Georgia, and we looked to the left and right to the outskirts of the diamond. The sudden switch from the lush greenery to this shabby road was another contrasting and opposed face of the jewel. Lasha always pronounced it Cowcassus, but he’s the native, and always spoke of them with such immense pride that we both followed suit, or tried to remember to do so.

After a while it seemed we’d come to the edge of a town, and so it was, the eastern edge of Kutaisi. But we started easing right, and kept doing so, and also going up. We rose and rose, swooping up, back out from rural streets to hills and trees again, and bridges across rivers. Finally, at some great height, we followed a stony path up to the monastery, yet another protected UNESCO site. There are four of these in Georgia, and we’d seen three in one day. Pulling up on an uncovered track, very loosely a car park, we got out and walked towards our final stop of the day. This is a large building, or set of buildings, consisting of the monastery itself, a smaller replica of it, a large hall, a belltower, an observatory, a wine cellar, and the monks’ quarters. Because this, like the basilica at Uplistsikhe and even the Jvari monastery, inside 12th century walls, is still an active place of worship. It was built by, and is the burial place of King David the Builder. As is the Georgian style, the main church itself was more square than stretched out – this is a Byzantine style, with archways within and without the buildings – and inside was just an incredible collection of frescoes, indeed every inch of the walls and ceilings was painted. In fact it’s one enormous mosaic, so impressive that it is known as ‘The centrepiece of Georgia’. Some parts had faded a little in the 900 years (!), but the overall effect was still stunning, like being inside an iridescent bauble. As well as King David, the tombs of ten famous rulers of Georgia are here, including, it’s said, that of ‘King’ Tamar.

This really was a special place, if slightly run-down between the ancient buildings, and high up here, we could just see the city of Kutaisi in a valley between the hills. We visited the hall, where kings of both sexes had gathered, and the observatory (the highest room of course, up a small iron spiral stairway). I think the other buildings were closed, and as we left, the bells went to call the monks to evening prayer.

Driving downhill now, we re-reached the edge of Kutaisi, and bumped slowly down cobbled streets very reminiscent of Montmartre and the Sacre Coeur on top of the hill there. Finally we came down to flatter, wider roads, and now squares and large roundabouts, and found our way to the Hotel Sani. It was around half 7 and definitely dusky.

We could have done with longer to clean up a bit after a long and dusty road, but there was a table booked at a nearby restaurant for 8pm. It wasn’t so nearby that Lasha was going to get in his car again, but I persuaded him that I’d pay for a cab, so he didn’t have to drive, and of course could have a drink with us! The cab cost three lari, 60p, and the driver refused to accept four. And the restaurant turned out to be exactly the one Helen had found for us, if Lasha had had other plans. And what a terrific place it was. Choosing upstairs as there seemed to be noisy music downstairs – a rowdy Georgian outfit after we’d eaten would have been terrific, but not the intrusive jazz that appeared to be going on – we sat in a big, whitewashed room with lots of space, and ordered away, wine first. But before I spout about the meal, there was a distraction. As we climbed the outdoor stairs up to the dining room there was an upturned half-piano, just the inner strings section, the perfect playground for the three tiny kittens that were clambering all over it. One black and white, and two white and black, they were particularly endearing, OK, gorgeous, and I knew I wouldn’t see much of Helen while we were here.

And about the wine, it’s a HUGE thing in Georgia. In fact they claim to have invented it, with remains of wine-making going back an incredible 7000 years. Initially, the wine was made in huge jars which they buried, for the fermentation process, and remnants of these jars have been found all over the country – there were lots and lots of them in the Gelati Monastery wine cellar, just lying around, broken and cracked. There’s even a school of thought that says that the very word wine comes from the Georgian word gvino. Under Soviet rule, only 2 grape varieties were recognised and widely drunk, in fact there were 500. As we drove out of Gori, every house had a large wooden frame in front, or to the side, on which trailed the family vines. So many families make their own individual wine, the variety and personalisation is immense, and not to be offered the house wine when you visit someone is virtually an insult. So the Georgian attitude, and that of Lasha to wine is one of deep pride. (Sign outside a restaurant in Tbilisi: SAVE THE EARTH. It’s the only planet with wine). But this is not a nation of drunks, a society which is in the mind’s eye like many eastern European countries, that of vodka-swilling depression and intoxication, it’s much more refined than that. They enjoy it more, similar in a way to the French, but without the haughty exclusivity. Having said that, over tonight’s meal, Lasha did say that it was a Georgian saying that ‘red is for tasting, white is for getting drunk’. Like Georgia itself, their wine is just not that well-known, and I personally can’t wait for the western world to really discover and start importing the stuff, because the result of all the history and widespread production is that Georgian wine is excellent. There are typical regional differences too, as well as the myriad nuances from house to house. The red wine of western Georgia is sweeter than that of the east, in fact it describes itself as semi-sweet, which is not my thing, but I had a glass with my main course and it was good, not too sweet after all, perhaps we’d ordered a dryish one, on Lasha’s recommendation. And the white wine of west Georgia is different too, darker in colour, amber in fact, and sourer.

In our restaurant, Palaty, we both ordered salad starters, mine the local version of the aubergine-and-walnut dish, and then both followed with fried chicken, in garlic, and in walnut sauce, the bazhe I mentioned earlier, containing blue fenugreek and marigold. All fantastic. At this point, in the middle of the meal, the waiter brought over a tray with three shot glasses. This was chacha, the national spirit. We all downed it in one and it was very nice indeed, much more tasty than a lot of more metallic liqueurs like Marc. Seemed a strange time to serve it, instead after the meal, but we didn’t argue. Pudding next? But Georgia, as Lasha explained, doesn’t really do desserts. It’s not like Italy with its tiramisu, zabaglione and cassata, or France with its crème brulee and iles flottant. From the Palaty menu you could choose from such efforts as Sour Milk with fruit/honey, or Pancakes, with either jam and and sour cream, or with cheese and ham. Then, in one-word items down the page, Dried Fruit, Jam, Almond, Fruit Salad. They’re not big on puds. So we didn’t have one, and returned to the hotel, via the kittens, for our trashy TV and an early night. That was Day One. Another big day tomorrow.

30th May

When looking at the photos of the hotels before we set off, one room had stood out, the breakfast room here at the Sani Hotel. It was utterly enclosed, windowless, with white tables with red borders, often placed as long benches to share with other breakfasting strangers. Not enticing at all. We went along the corridor to this room and it was as portrayed, but I have to say that by this time, we were both on such a holiday high, and had realised that we were really doing something special with this trip, it didn’t matter in the slightest. No breakfast dungeon in the world could have taken the edge of the experience we were having, so we had our bits and pieces, teas and coffees, and were off with Lasha by 9 I think.

First stop the Prometheus Caves, on the outskirts of Kutaisi. On the way there we drove through a large area that was in darker days a holiday home area for Soviet officials, a sort of inland Costa del Kutaisi, and now it was run-down. The architecture was Soviet: concrete, straight-lined, and sharp-cornered, there were villas with now-overgrown gardens, for a holiday area it seemed pretty harsh, yet they swanned into the area, built the community for themselves, then abandoned it. The Russians were still coming out of this trip pretty badly.

Inside the entrance to the Prometheus Caves, we were the only two English-speakers, the rest of the tour crowd were one group, I’m not sure where from. But no-one had told the guide about us, that she needed to do her talks twice, once for them, once for us. The caves themselves were spectacular, but we missed out on any historical or archaeological information because she would deliver her speech in Georgian, or it may have been Russian, then the whole group shuffled off. So I spent the first 15 minutes desperately trying to catch up from the very back to the guide at the very front, and in caves in the dark, on narrow pathways that mostly had room for one person to walk, and with rock pools often on either side, this was a bit of a scramble. Eventually I caught up with her when we came to a wide cavern where we could all assemble, and after her speech I grabbed her attention and explained. She was mortified. She’d had no idea, and should have been told by the people upstairs. So Helen caught up, and the girl quickly went through highlights of what we’d missed so far (about 3 information stops) and from then on looked after us very well indeed.

The caves were really something, they went on for ages, and were long wide tunnels of brightly-lit stalagtites and mites, subterranean rivers and deep pools, incredible rock formations and even ancient cave drawings on the walls. One rock formation, a giant bulb that towered over us in a cavern was known as The Jellyfish, as its rock tentacles, twenty feet long drooped down from its head; the tentacles were thick and meaty, I thought they looked more like dreadlocks. The tunnels and ceilings were all lit up in iridescent colours so it really felt like we were walking through a fantasy world. The whole place, as all underground caves do, turned me into a boy again, I don’t know what I read at that age but the feeling is very childlike and full of adventure and danger. I could write a thousand words about the caves but Helen’s pictures tell the story better. You know what they say.

At the end of the tour there was a long, man-made tunnel towards the light, and by this time the guide was walking along with us. Just before the end, she stopped and showed us the wall to the right, protected by net wiring. In the rock face there were lots of tiny, tiny flashes. ‘These are diamonds’ she said, and helped Helen get the light right for a picture. In the end she looked after us more than the big group, and this secret ending was just for us.

Back at the car park (we all got in a large minibus to take us back to the start) we waited for Lasha to appear, I think he used the various excursions where he wasn’t the guide to do a bit of admin, and he soon emerged from the main building. We set off on another long-haul drive, jumping from piece to piece of the jigsaw, from the ex-Communist commune on the edge of Kutaisi, back through the green and fertile forests, through the tunnel to east Georgia again and out onto the open road following the ancient trade route. Before we got to the east however, to the tunnel, we stopped for lunch, it was easily 1 o’clock by now.

I had vaguely wondered where on earth we were going to find anywhere to eat in the middle of this huge section of trees, but suddenly he pulled over to the right and down a lane. At the bottom was a large wooden open cabin, a wide space with room for about twenty solid tables. This was on a raised floor, with trees nearby and foliage, probably more vines, twisting round the roof and quite honestly, in this lunchtime sun and peace, it could have been a shack in Polynesia. It was called the Fairytale restaurant. We chose a small table just outside, the sun wasn’t too hot for that, and saw that the whole building was set overlooking the bank of a river, deep in the valley with the trees edging up the far side. What a wonderful location and surprise.

Helen ate pork barbecue, and asked for a highly-recommended tomato sauce on the side. Both were ideal, the pork chunks tasty with a few fried onion strands, and the tomato sauce like nothing ever from a bottle, made from those incredible Georgian tomatoes. She drank beer, and sticking to our format, I had wine, the western version of white, dark and slightly sherryish. I ordered the lamb chakhapuli, the meat, sour plum and tarragon stew, for the wine to cut through. But as had happened before when one of us had ordered lamb from a menu, I was told they didn’t have any. Lamb isn’t big in Georgia, explained Lasha, restaurants have maybe one dish on their menus but don’t really expect them to necessarily have it in the kitchen that day. Lasha himself, as last night, ate lightly, mostly bread and cheeses. For a big fellow he didn’t eat a great deal. Here also was our first taste of tarragon lemonade, an amazing vivid green drink, sweet but undoubtedly tasting of the aniseedy herb. After this we ordered it at most meals.

We followed our Silk Road back, almost as far as Tbilisi, then turned left, north, up towards the towering Caucasus mountains. Another jigsaw piece. This road was for a long time dotted on both sides with rather shabby stalls, selling nothing important, just touristy or wayside goods, fruit, ice-cream, souvenirs (those white Cossack wigs and ‘Georgian snickers’ were everywhere) and other bits and pieces; this road reminded me of one in Burma, that I’d been taken along for half an hour on the back of a moped, a lot less squalid than that though, just impoverished and hopeful traders, a cross between Burma and Blackpool. Then the traders vanished behind us, we were on open road again, and the hills started to rise around us. Before we came to our next main stop, we paused at the Zhinvali reservoir. Shades of Kielder water, but much more dramatic, perhaps more like Lugano in colour and surroundings. A huge body of water, stretching off into the distance in two directions between tall wooded hills, mountains almost. But like Kielder, there is indeed a village under the water…

Along this road, and yesterday from Gori onwards, there were often fields with eyecatching sprays of flowers across them, always red and purple, wide swathes of colour to the left and right. We carried on and reached Ananuri Castle, on the shore at the end of the reservoir. This is a 13th century fortress, complete with frescoes and a cross dome church, that has seen its share of attacks over the centuries, but is another that has survived with some majesty to this day. The outer walls of the church are highly decorated, with St. Nino’s grapevine cross on the south side. Overlooking the water from high above, it’s a spectacular site.

Back in the car and we were certainly starting to climb now, and a feature of Georgia soon become more apparent, and dangerous. The roads are terrible. Often, in built-up areas, or car parks, Lasha had to edge the car forward, jinking between huge holes in the ground. The highways themselves are less scarred by the giant potholes, but that only encourages people to drive faster, and to follow the rules of the road at higher speeds. Unfortunately, the rules of the road seem to vary from car to car, and as we started rising into the mountainous roads things got distinctly alarming. There was a comedy moment quite soon, as a small, decrepit old black Lada pulled out in front of us and then failed to accelerate to the speed of the road. Helen spotted why. ‘How many people are in that car?’ she said, and we all burst out laughing. We could see at least seven heads, blocking our view through the car itself, it was crammed. Of course it turned back off the road at the very next junction, only about a hundred yards away, and then we could also see that though the back and passenger seats were full of bodies the actual driver himself was a huge fat man. The fact that it was Russian car added to Lasha’s fun, and everywhere, these cars are considered by Georgians to be a laughing stock.

But the laughing was soon quelled by what was going in front of us, and around us. The mountain road seem to change randomly from two lanes to three, with the unbroken no-overtaking line in place only sporadically. This didn’t matter anyway, as no-one took any notice of it, and the overtaking that was going on, from both sides of the road, was increasingly scary. Lasha, phew, was a much more mature driver and never attempted anything stupid, but there were a few, a lot of very close calls. A car would come zooming past us, and we could see one on the other side doing the same. At the last minute, both subsided back into their lanes, but it was so often very close indeed. If the gap was wide enough between us and the lorry in front, cars would often nip out, round us and nip back in again, in an almost sideways movement, and carry on up the road like motorised dragonflies. And it wasn’t just the cars, whole articulated lorries often took upon themselves to try the manoeuvre, hauling their giant bodies out into the middle of the road and attempting a flash of acceleration which clearly was only going to result in a lumbering surge forward. Their great clumsy efforts were of course even more dramatic and frightening than the small cars, and like them, it was often a close call when they heaved themselves back onto the right side the road. Hippos and dragonflies. The mood in our car was by now one of nervous laughter at the preposterousness of what was going on. Lasha was used to it, and his laughter was resigned, but we were increasingly incredulous.

And there was a further factor, which now made the situation slightly surreal. As we were climbing on upwards to the mountains, the roads became more winding, as roads have to do at altitude. So now we would be doing 300-yard stretches, then a turn, often a hairpin, then another stretch, and so on. Perhaps not on the hairpins, but on the wider turns, neither cars nor lorries were deterred from their overtaking policy. Several times I couldn’t believe it as a lorry in front of pulled out, yet I could see that this section of road ended 50 yards ahead, the blind turn was imminent yet off they went. I don’t know how it happened but we never did see a crash. They must happen. You’d think the roadside would be a graveyard for crushed Ladas.

We were by now definitely Alpine, and starting to reach the roof of the country, among high peaks and looking up to further ones. We started to come to a town. Incredibly, up here we passed both an Indian restaurant and a Pakistani restaurant. And looking up the winding road above us, spectacular in its location looking out over and above everything, was a huge long chalet, our hotel! During this trip, even having seen the pictures of the hotel at home, I wasn’t ready for anything as spectacular and dramatic as this, it was magnificent. And with some considerable glee, we opened the back door of our room to find ourselves on a balcony which extended along the whole floor, and looked out over an enormous panorama of mountains, as far as you could see, left and right to distant valleys and pastures, down to the road we had climbed, and up to the peaks opposite. Breathtaking. And a spot of luxury and privilege I wasn’t expecting anywhere in this country. We were very excited.

Helen wandered off a little to get more camera angles, I sat down at the table outside the room. Soon I felt a nuzzling on my leg, and looked down into the huge face of a wolf. It stared up at me inquisitively. I really don’t seem to be one for alarmed gestures nowadays (see the cows in the forest episode), and I hope this non-reaction won’t cost me in the future, but whilst quickly trying to remember from boyhood stories whether wolves eat people, or perhaps whether they used to but don’t now for some reason, maybe modern wolves don’t eat people, it’s 2019 after all, and where’s the forest that you’ve come out of? Don’t you live in a forest? Not on the balcony of a hotel – there were a lot of thoughts in that millisecond – all that came out of my mouth was ‘Are you a wolf?’ I think maybe I imagined that talking to it like a child, in a friendly voice might dissuade it from taking a bite out of me and calling the rest of the gang. But it was of course a huge huskie, with a wiry white coat when I stroked him, or her. It hung around for a bit, not particularly impressed with my pathetic patting, then decided my shoes might be tasty. It was starting to really nibble when I got up and went indoors.

It was very much a chalet, this hotel, catering for skiers and skiing parties, of which in these mountains there are lots. Even in late May there was snow on the high peaks. However, today there seemed to be only about a dozen people staying here, and consequently a buffet had been set up downstairs and the kitchen staff had gone home, fair enough. The three of us sat in the open room/restaurant and helped ourselves casually to the various items on offer, simple stuff: some braised beef, fried trout, soup, cheeses and bread, salads, and bought a bottle of white wine from the bar lady. As yesterday, we were all fairly tired and didn’t want to be too late, so Helen and I did our usual thing of buying another bottle of wine and taking it to the room, to fade out watching whatever we could find on the telly.

31st May

We both found ourselves awake at around 5ish next morning, if only briefly, and sat outside in the mountain air as the light started to come up. Below, only the occasional lorry twisted up the looping road, turning sleepily in the half-light. At intervals, you could slip out and watch the sun creeping down the sides of the mountains opposite, watch the day dawning on this majestic scene. Breakfast downstairs again, only the view from the table was much clearer than last night. Along with the usual cereals, croissants and jams, there was Georgian bread stuffed with spinach and cheese, a version of khachapuri, shaped like a slice of pizza, which was surprisingly light.

Onwards and upwards. Today we would drive right up to the northern tip of the country, to the border, to the most spectacular and extreme scenery of the trip. In a hobbit-like trek, we drove on to high plateaux, down past green pastures, wide valleys and mountain streams. There were several rafting centres set up by the tumbling river, where the water flowed swiftly over its shallow bed. The road was much less busy today, and there was a lot more space on either side as we climbed on. A couple of times there were alternative roads, that drove into long tunnels. This was because in winter, the patch we were currently on would be under several metres of snow. At one point, away to our left across a wide gorge, we could see a remote village, reminiscent of such places in the Faroes, and Lasha said that for the people here, winter was very hard. Sitting on their plain, they can be cut off by snow for months. Sounding proud of the hardiness of these Georgian highland tribes, Lasha reeled off a quick list of a few of them, in an impressive volley of glottal exhibitionism. Looking into it, he may have talked of the tribes of Svanati, Khevsureti, Kakheti, Adyghe, Durdzuks and Khamekits but I’ve no idea. It was quite a sentence though.

We came to a small town called Gergeti, and turned left. The road climbed up and up, and I could see where we were heading. I’d seen it from the car about a mile ago, but haven’t even bothered to ask if we were going there, it was surely way too high above us. But we were. Because of its setting, the Gergeti Trinity Church was the most amazing of all the buildings we’d visited. It’s over 2000 metres above sea level, perched on a hill amongst the mountains. Those mountains themselves are dwarfed by Mount Kazbegi, which towered over the entire vast scene at over 5000 metres, the third-highest peak in Georgia. The road twisted up through woods at one point, and we passed two sets of travellers, one a group of young hikers, who were tackling the slope straight up, ignoring the road, and the other a family, with two children, who were labouring along the side of the road. They had a long way to go. Up until only 6 months ago, walking was the only way to get up here, the road was only built at the end of last year. Eventually we came out into the clear and emerged at the foot of the church’s hill. We parked and walked up the steps to the building, finally atop this incredible scenery, apart from the huge mountain behind us. It’s hard to describe the impact of this place. And we’d been unbelievably fortunate, again. The vast majority of the time, Mount Kazbegi is shrouded in cloud, that’s if you can see it at all. Even its Wiki picture has clouds in it. Today was utterly clear, we could see everything from the hill, and the outline of the white mountain against the blue sky was cut glass. With your back to the mountain you could see down to the town and across to the mountains on the far side, who knows how far away they were, the whole vista was gigantic. (The town seems to be known as Gergeti, and also Kazbegi, because of its nearby church and mountain, but it also seems to be called Stepantsminda. I don’t know.)

The church was built in the 1300s and, like others on our travels, is still an active Georgian Orthadox church. In times of threat, the relics in Mtskheta were brought all the way up here for safety, including St. Nino’s cross. It is similar inside to other churches and monasteries we’d visited, but with its location up here, it felt more ghostly. As I left I noticed that the sun was shining through a high window, casting a bright shaft exactly down onto the doorway. I wondered if the exact placing of this window, and possibly the building itself, was astronomically precise and deliberate. The site is in fact two buildings, the church and the bell tower, and sitting up here with its panoramic view it has become a symbol of Georgia itself. And as we stood inside the quiet, sacred church, Lasha said that of all places in the country, here was where he felt his heritage lay, here was where he was proudest.

Helen didn’t hear Lasha asking us to come back to the car, and lucky for her she didn’t as she went to take more pictures of the view, and two eagles flew past! So fast that she couldn’t catch them on camera, but really close.

We didn’t stay here for a particularly long time, but it’s probably the most immediate visual memory of the whole week.

Pushing on, and back down to the main road, we turned left and headed north, and only a few miles away is as far north as you can go in this part of Georgia. We stopped at another church. The road had flattened out by now, and it and the nearby river were dashing headlong towards a huge rock face. There must have been a way through for both of them, because on the other side was Russia. About half a mile away we could see the border. It was quite an imposing idea, all the might and power of Russia ancient and modern was just behind that cliff. Even the rocks looked forbidding. So we stopped briefly and wandered round, not in, the church, turned our backs on Putin and headed back up the road.

Soon we came to a waterfall, where we’d decided to stop. It was a bit of a hike, uphill, and Helen decided she was too tired and would give it a miss. I only just made it, taking several breaks with Lasha on the way, but I guess like in the Prometheus caves, some boyish instinct kept me going. At the top it wasn’t the biggest waterfall I’d ever seen, but a healthy cascade amongst the surrounding woods and rocks. The fall itself landed in a pool just across a stream, and- wait a minute, Lasha started crossing the stream, in time-honoured boyish way, by using stepping stones. I hadn’t planned on getting that close to the spray, in fact back in the car there was some joke about the two us standing underneath the fall itself, but it looked like that’s where he was heading. Boyishness to the fore, and although my brain told me that I really ought to be very careful here, there was never a doubt I was going to follow him. A slip and tumble into the stream age 8 and you merely get wet and perhaps scrape a knee or something, age 53 and your clothes get soggy and stay soggy, and I could bash a wrist or crack something. Steady. But the stones were solid, not rickety, and soon I was standing within a dozen feet of the pool where the waterfall landed, well within spraying distance. Definitely an experience to savour, in fact I should video it. This involved getting my phone out of my shirt pocket, wiping it clear, trying to find the phone icon on the screen, getting my glasses out so I could find the phone icon on the screen, wiping them clear, finding the icon, putting the glasses away, then checking to see if I was on the Camera or Video setting, getting my glasses out again, turning my back on the waterfall, wiping the glasses clear, finding the setting, putting my glasses away again, and turning to face the falls. But the atmosphere, the closeness and wetness of the tumbling water, the splashes on the phone lens and on my clothes, it was all great fun.

Lasha gave me a hand re-crossing the stepping stones, and we headed back down the path, still feeling quite excitable. As several 70 year-olds strode up the path and round us without panting, I retracted my complaint on the way up about being nearly twice Lasha’s age. And my clothes didn’t stay soggy, the sun, even at this altitude, was easily hot enough for me to be dried out by the time we reached the car. Helen had been happily organising photos, and she was re-assured by the sight of me about her decision not to tramp up half a mile of stony path to get soaked.

A little further on, further back down the road south, past the Gelgeti Church and towering Kazbegi (still as clear as a bell), we stopped for lunch, and after this morning, we were ready for it. In warm sun, we sat outside at one of the bench tables and ordered cool beers. Lasha stuck to bread and cheese diet, Helen to her veal barbecue, with tkemali, sour plum sauce this time, and I had more fried chicken in bazhe. All three days, Lasha had pointed out the ‘walnuts trees’ everywhere we went, and it’s certainly a huge ingredient in Georgian cuisine. I switched to white wine, the paler, eastern variety this time, took the flesh off the chicken bones and I had what looked like a dark korma. My sort of lunch. And Helen’s veal barbecue didn’t disappoint either, really flavoursome meat, again with strands of slightly-burnt onion strands and the little boat of fresh green sauce. Great lunch.

On the way up we’d passed an obvious stop-off, a tourist attraction, Lasha had told us what it was and we decided to visit on the way back if there was time, and the time was now. This was the Friendship Monument. It’s a semicirclar installation built in 1983 to mark the 200th anniversary of a mutual treaty signed between Georgia and Russia. The mural tells the story of the two nations in the intervening 200 years, it cites some poetry of Shota Rustaveli, and is rather dramatic, busy, brightly coloured and beautiful. But hold on. The Friendship Monument? These are the guys who whitewashed all the frescoes in a medieval church and national treasure for a state visit that never happened. The guys that went back on the 1783 treaty within twenty years of signing it and annexed Georgia in 1801. The guys that even now occupy 20% of the country. The monument itself is still there. Of course. It’d be asking for too much trouble if anyone were to damage it or try to remove it. But the Georgians are not happy. They don’t even call it The Friendship Monument, they call it The Viewpoint which, sitting overlooking a huge valley, it is. But it’s not on my Georgian map.

And that was it really, as far as sightseeing goes. We headed back south, the road dipped, and we retraced our way back down, past our spectacular hotel, down the corkscrew road, out into flatter country past the castle and the reservoir, whilst being overtaken at high speeds all the time, and finally along past the street sellers to the junction. This time we carried on, back to Tbilisi, and before we knew it we were in traffic on David the Builder Avenue, then up through Liberty Square with St. George golden in the late afternoon sun, and finally we arrived back at the Hotel Citrus. What a breathtaking journey, and few days it had been! Three days felt like three weeks, and we’d covered over 1200 kilometres, and seen so many things. We thanked Lasha profusely, he had been the best we could have hoped for, easy company, professional, extremely informative but managing to get all his facts in in such a friendly way, that can’t be easy. He drove off, though we would see him again as he’d told us he was to be the driver to take us to the airport in a couple of days time.

We’d had enough adventure for today, and after resettling in our room (they gave us the same one, which was nice.) we sat down in the bar and started to collate photos and notes. Sitting there, in the comfy bar of our hotel in the capital, it was almost impossible to think that we’d woken up high up in the mountains with that view, or that from there we’d gone to Russia, and only about 6 hours ago we’d been standing up at the incredible Gergeti Church, on its mound amongst the mountains, and with the gleaming slopes, presence and majesty of Mt. Kazbeki behind us like a Caucasian Kilimanjaro.

1st June

Next morning we had another trip, and we waited downstairs at 10am for George, the guy who’d picked us up from the airport at 5 in the morning about a month five days ago. He was to show us round Tbilisi, it was part of the same package as the tour we’d just come back from. First we drove to the Holy Trinity Cathedral. We’d seen pictures of this huge edifice standing out clearly in the town, dwarfing the surrounding buildings like a sphinx amongst the hovels of Cairo. We headed down the David the Builder Avenue once more, then turned across the river, and soon we were in back streets, dusty and run-down, it really felt like a middle eastern souk round here. But then the cathedral suddenly appeared to our right, and we pulled into the big space in front of the gates. We went through the archway and faced the huge building (it holds 10,000 people). It was pretty hot already today, and after climbing the set of steps it was lovely and cool as we went into the semi-darkness. There was some loud singing going on, male voices, with seemingly ancient and traditional harmonies enhanced (for me anyway) by occasional shafts of dissonance, more modern unresolved suspensions and unexpected lines. It sounded like about 40 men singing, but as we went further in I could see just three, huddled together in their robes round a microphone. Most of the people inside were just standing listening, admiring the building and all its decoration, but not moving anywhere.

This cathedral, after the all the history we’d seen in the last three days, is ridiculously new, it was finished in 2004. It took nine years to build, the foundations having been laid in 1995. This followed the end of Soviet rule in 1989, but these years were a time of huge unrest for Georgia, and so by the time the cathedral was eventually completed it was seen as something of a symbol of Georgian independence and unification. As I say, it’s vast, and is in fact two churches in one. After listening to the gorgeous music for a while, George told us there was another cathedral downstairs! Drifting out the back of the room upstairs, we came out into a wide, marble area, in the middle of which was a staircase. This led down to a chamber which became the balcony overlooking the central area of an entirely different church, with its own music and people praying and lighting candles. Feeling particularly perceptive and controversial this morning, I mentioned that I’d noticed that upstairs was mostly men and down here seemed mostly to be women. ‘It’s just a coincidence’ said George, smiling. He was a smaller man than Lasha, bearded, young, with a deep voice that seemed appropriate in the present surroundings at least.

Coming out into the hot sun we headed towards the car. We left the dusty Kasbah streets and headed round towards the river, and parked in a street above it. We walked down to Metekhi Church. This is built on the cliff on the bank of the river (the same Mtkvari river that stretches inland to Mtshketa and the cave city at Uplistsikhe). There’s a lot going on here. Firstly, near the church, there is a huge statue, of King Vakhtang Gorgosali, the founder of Tbilisi. He sits astride his horse looking across the river to the Old Town because here, legend has it, he went hunting and shot a pheasant with his arrow. His hunting falcon chased to capture it, but in the struggle, both birds fell into a hot sulphur spring and died. But the king was so impressed with the discovery of the springs that he decided that here would be a good place to build a town, so he did. At this point a thought struck me, and I asked George what the word ‘Tbilisi’ meant, and this time he gave exactly the answer I was hoping for: it means ‘warm water’. Well done me! And even today, the falcon is a symbol of Tbilisi, and it’s on the Emblem of the city, as well as having various statues dotted around. As we stood next to the statue today, George pointed out the strange stonework down at the river’s edge on the far side. Nearby it’s the same on our side, a rough, rocky bank, but definitely looking like the foundations of something, several metres above the grey water level. These are the remains of an ancient market area, that the Silk Road traders used to use – again, that glimpse of them, emerging to give us a picture of the past.

The church itself has a story. For centuries there were other buildings surrounding it, a citadel, protecting it and shoring up its position on the cliff edge. Then along came the Russians, who decided that it shouldn’t be used for religious purposes (this was after they broke the Treaty of 1783) and they used it as a barracks, and they demolished the citadel. Sometime later they built another building by the church, which they used as a prison. They knocked that down when they’d finished with it. Like the whitewashing at Mtskheta cathedral, such dismissive and destructive abuse of sacred ground and ancient beauty. Where’s that Friendship Monument again?

The church itself survives, and is beautiful inside, and on a day like today, cooling. Communion was taking place while we were there, and a busy queue was only part of the throng in there. On benches at the back sat rows of women. I asked George about this, but he said they were just waiting for their friends, they weren’t praying. After what he’d told us about the flagrant Russian destruction right outside, which made me quite angry, the building, now returned to its full religious purposes, seemed like an oasis amongst evil and indifference.

We headed towards the cable car now, which was to take us up over the Mtkvari to the battlements (the Narikala Fortress) high above and behind the Old Town. But two interesting spots just in the short walk to the cable car station. First, George walked us over to a long chunk of concrete, placed there for show. As we approached it it looked vaguely familiar, and of course it was small piece of the Berlin Wall. So appropriate. I presume all ex-Soviet capitals have a piece, it’s such a symbol, of so many things. And crossing the road, there was a piece of art, a metal tree with lamps hanging from the twisted branches. I thought it was quite pretty, but then George pointed out a man standing by the tree, who I somehow hadn’t noticed. He stood proudly in a white Soviet uniform, stripes on the shoulders, a military hat, a healthy moustache; yes, he was dressed as Stalin. I couldn’t believe it. Again, like the slightly suppressed attitude at the museum, the reluctance on Lasha’s part to become even flushed about the man (though of course he may well have just been being professional with us, and not becoming upsettingly irate. Though I felt there was something there, but people just can’t say…), here was history, in its worst form, being presented in broad daylight and no-one could say a thing, indeed the man seemed almost popular, having his photo taken. There are frightening undercurrents in Georgia.

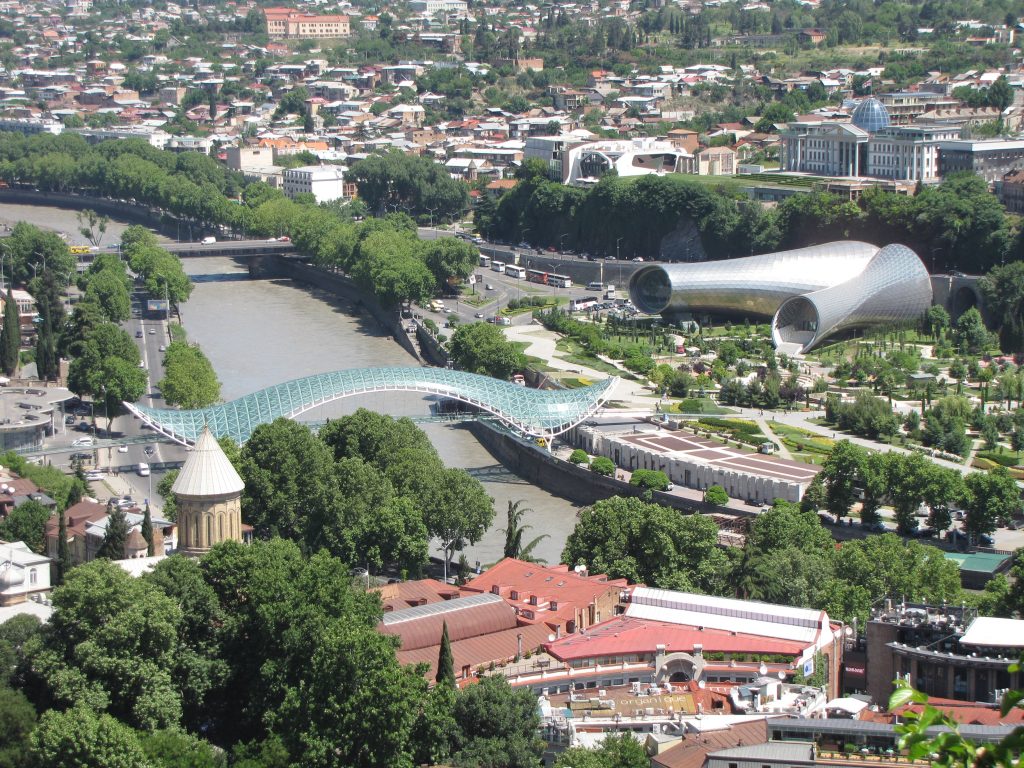

The cable car rose quickly over the river, out above the Old Town, complete with its sulphur baths, still steaming under their domed lids to this day, and up to the fortress above the city. Yet another high viewpoint in this city, it seems to be a place of extreme ups and downs, while still somehow being compact, with colourful red and darker old houses and very recent bridges and monuments. We clambered around the ruins a bit, a very large lizard basked in the sun on the rocks, and came to a lower street. From here a short walk back up to the entrance to the Botanical Gardens – a trek for tomorrow – then down a spiral ladder right down to a bridge over a steam. We were now back down at ground level, but we tried to stay inconspicuous as there was a wedding shoot taking place on the bridge. We went up the steam to a waterfall, about the same size as the one up in the mountains, and a dog stood absolutely still in the water, cooling his paws up to the knee. Following the river back round to the town, it became more walled-in, like a canal, and there was a tremendous croaking and belching from some obviously very large frogs by the water.

We came round to the front of a temple, called the Persian House, decorated in intricate purple and orange like the mosques of Samarkand. Then a short wander through the streets of the Old Town, including the very courtyard and house where George was born and brought up (my excited gag of ‘You’ve come a long way!’ went un-noticed, possibly a good thing), and came to Sioni monastery. Although the original church was built by King Gorgosali in the 5th century, the structure today was built in 1112 by David the Builder and the foundations of this can still be seen as the lower stones of the buildings. There was a tremendous volume of singing coming from inside, but the place was too busy for us to go in and investigate, and besides, it was time for a rest and a drink.

A little further up the downtown area, heading slowly up the street that would lead to Liberty Square, we saw a street of restaurants on either side, and we turned in there, settling at one nearby that blasted mists of cool water into the air every 10 seconds or so, a very attractive feature on a day like this. We rested here for a while, ordering beers, wine, and more of that amazing tarragon lemonade, all very refreshing. Before long we headed back down the road to the Sioni monastery, and this time we could go in, as it was much less busy, Helen having her necessary scarf with her at all times by now. Another cooling and beautiful square room, a cross-cupola dome this time. A priest was reciting from a scroll, singing short rising and falling phrases. A man stood right next to him, holding an incense burner. The smell was sweet, and I stood quite close for a while, almost mesmerised, watching the priest chanting his lines in the corner of the church. After a while, we milled around briefly inside, and came out the side door. Music was still going outside, taped music now, which was fed through the speakers all round the square in which the church sat, you could see the speakers attached to trees and railings.

Heading back uphill once more, there was suddenly a commotion right in front of us. An old orthodox Jew, a priest, perhaps, dressed in his black robes with his silvery beard was accosted by a loud old woman clutching a bunch of bank notes. These she wanted him to have, but he was adamant that he didn’t want them, but she absolutely insisted, and the thing became quite physical as he tried to escape. But I think she won, as she rammed them into some part of his robe and broke free and away. He was distraught, really downed by this. I asked George what his protestations had been, and he said that the priest had been shouting ‘I have enough, I don’t want this, I have enough!’, but she wouldn’t have it, and was determined to make her offering. Quite a scuffle really.